The fashion industry is a complex ecosystem, spanning from exclusive handcrafted luxury to mass-produced affordability. This blog explores the stark contrasts between haute couture and fast fashion, while contextualizing their roles alongside ready-to-wear (RTW) and designer brands.

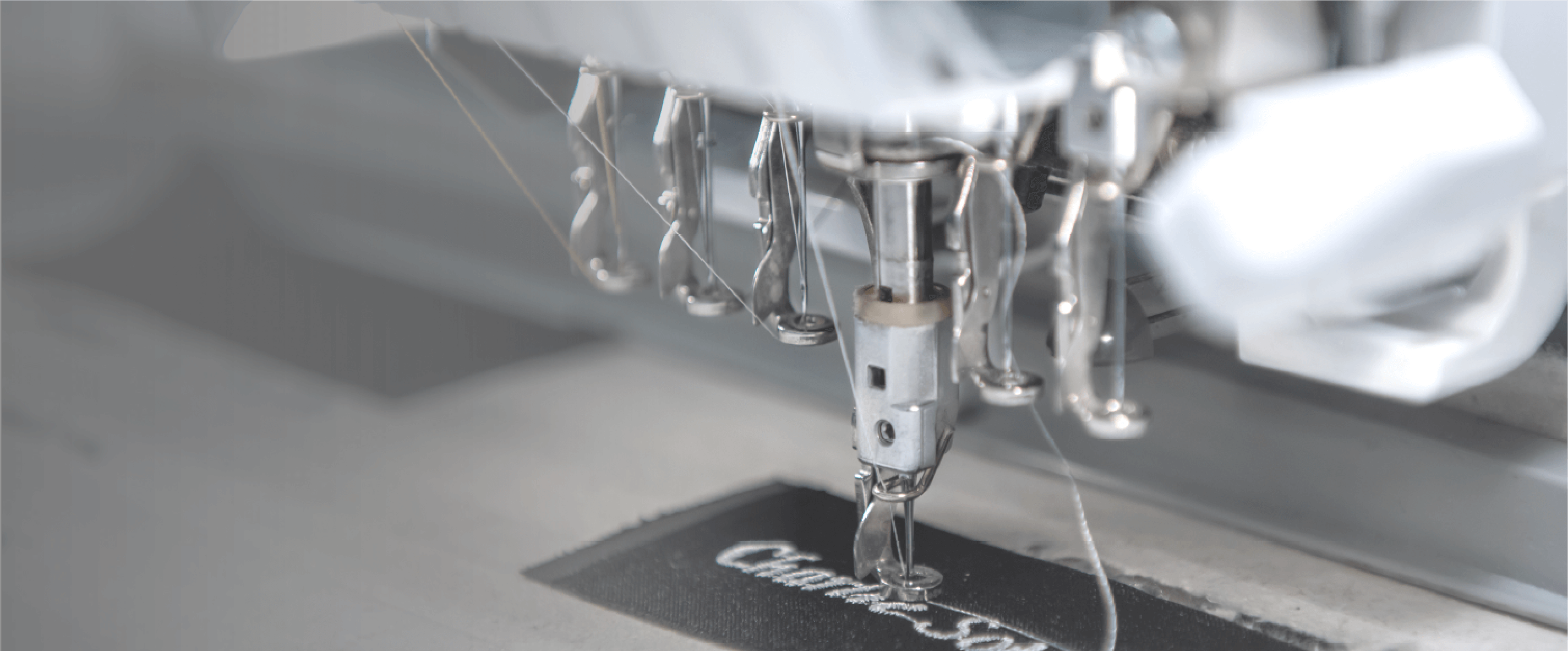

Haute couture (French for "high dressmaking") represents fashion’s most elite tier. Each garment is handmade for a specific client, using luxurious fabrics like silk, lace, and hand-embroidered embellishments. Couture adheres to strict guidelines set by France’s Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, ensuring only approved houses (e.g., Chanel, Dior) can use the label. A single piece can take hundreds of hours to create, with prices starting at $25,000.

For those seeking similar craftsmanship on a smaller scale, custom clothing manufacturers offer tailored solutions that balance quality and affordability.

Designer brands like Gucci and Prada occupy the tier below haute couture. Their ready-to-wear (RTW) collections blend creativity with practicality, offering high-quality, trend-driven pieces at accessible (but still premium) prices. Unlike couture, RTW garments are produced in limited quantities for department stores and boutiques, targeting fashion-forward consumers who value both aesthetics and functionality.

Fast fashion—exemplified by brands like SHEIN and H&M—prioritizes speed and low cost. Garments are churned out in factories using cheap labor and synthetic materials, often replicating runway designs within weeks. While democratizing access to trends, this model fuels overconsumption: the average fast fashion item is worn just 7–10 times before being discarded.

Haute couture traces its origins to 19th-century Paris, where Charles Frederick Worth became the first designer to sew labels into his creations. Historically, it served European royalty and elites like Louis XIV, who used clothing to project power. Today, couture remains a status symbol for celebrities (e.g., Lil Nas X’s 2021 Met Gala Versace armor) and billionaires.

For modern consumers, custom formal wear offers a way to capture this exclusivity for special occasions like weddings or galas.

Fast fashion emerged in the 1970s but exploded in the 2000s with globalization and social media. Platforms like Instagram accelerated trend cycles, normalizing a “wear-once” mentality. Brands like Zara mastered “micro-seasons,” releasing 36 collections yearly to capitalize on fleeting trends.

Couture garments begin with sketches, followed by meticulous fabric selection and multiple client fittings. Master artisans hand-cut and sew each piece, ensuring precision—a stark contrast to fast fashion’s automated assembly lines. As one article notes, “A couture dress outlives its wearer, often becoming an heirloom.”

Fast fashion relies on global supply chains to minimize costs. Polyester and nylon—derived from fossil fuels—account for 60% of materials, while toxic dyes pollute waterways. Garments are often produced in sweatshops, where workers earn less than $3/day. This model generates 92 million tons of textile waste annually.

Couture and designer brands thrive on scarcity. A 25,000 gown isn’t just clothing—it’s art. Meanwhile, RTW caters to aspirational shoppers willing to splurge on a 2,000 Prada bag. Fast fashion, however, thrives on volume: a $10 shirt may seem affordable, but its hidden environmental and social costs are staggering.

Couture clients seek self-expression through unique pieces, while fast fashion shoppers chase the dopamine rush of newness. As Marc Jacobs noted, “Fashion is a whim—you don’t need it, you want it.” This dichotomy highlights deeper cultural values: craftsmanship versus convenience, permanence versus disposability.

Fast fashion contributes 10% of global carbon emissions and 20% of wastewater. Less than 1% of materials are recycled, with 85% ending up in landfills. While brands like H&M launch “eco-collections,” critics argue this is greenwashing—distracting from systemic overproduction.

Couture’s made-to-order model minimizes waste, offering lessons for sustainable fashion. Emerging brands are adopting bespoke practices, using deadstock fabrics or upcycling vintage materials. However, scaling these methods remains challenging.

Designer brands are increasingly embracing sustainability. Stella McCartney pioneers vegan leather, while Patagonia repairs garments to extend their lifespan. RTW brands like Eileen Fisher now offer recycling programs, signaling a shift toward circular fashion.

Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z, are rejecting fast fashion’s excess. Platforms like Depop and Vinted promote secondhand shopping, while hashtags like #HauteCouture inspire appreciation for craftsmanship. The “buy less, buy better” mantra is gaining traction.

Technology could revolutionize sustainability: 3D printing reduces fabric waste, while blockchain ensures supply chain transparency. Meanwhile, certifications like Fair Trade and B Corp help consumers identify ethical brands.

Haute couture and fast fashion represent the two poles of an industry at a crossroads. If couture is artistry and legacy, fast fashion represents the instant gratification demanded by modernity. The rise of sustainable RTW and designer brands offers a middle path: one that balances creativity, accessibility, and responsibility. As consumers and brands alike put a premium on ethics, the future of fashion may finally align with the health of our planet.

Haute couture refers to exclusive, handmade garments tailored for individual clients using luxury materials, adhering to strict French legal standards (e.g., Chanel, Dior). Designer clothing, while high-end and creative, is mass-produced in limited quantities (e.g., Gucci RTW collections) and sold at premium prices. The key distinction lies in customization: couture is one-of-a-kind, while designer pieces are standardized.

Fast fashion relies on synthetic fabrics (e.g., polyester), which shed microplastics and take centuries to decompose. It also generates massive waste—92 million tons of textiles end up in landfills yearly—and uses toxic dyes that pollute waterways. Additionally, its rapid production cycles encourage overconsumption, with garments worn only 7–10 times on average.

Look for certifications like Fair Trade, GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard), or B Corp. Sustainable brands often:

• Use organic/recycled materials (e.g., Patagonia’s recycled polyester).

• Practice transparency in supply chains (e.g., Everlane).

• Offer repair/recycling programs (e.g., Eileen Fisher).

Avoid brands promoting “micro-seasons” or ultra-cheap prices, as these signal unsustainable practices.

No. RTW refers to pre-designed, factory-made clothing sold in standard sizes (e.g., Prada’s runway collections). While RTW is mass-produced, it prioritizes quality and timelessness over speed. Fast fashion, however, focuses on copying trends rapidly with cheap materials (e.g., SHEIN’s 10,000+ weekly styles). RTW is pricier but more durable.

Haute couture’s price reflects handcrafted artistry:

• A single gown can take 200+ hours to make.

• Materials like hand-embroidered lace or silk can cost thousands alone.

• Only ~2,000 clients worldwide can afford it, limiting economies of scale.

Each piece is an heirloom, designed to last decades—unlike fast fashion’s disposable items.